Spanish Old Master Drawings

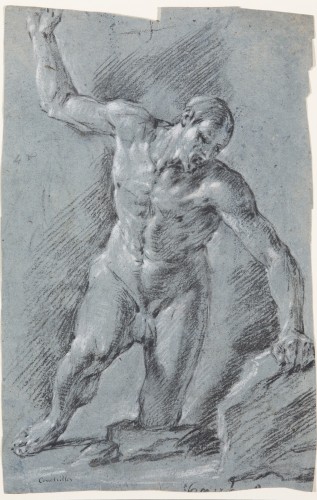

Academic Study

Juan Conchillos

(Valencia, 1641-1711)

- Date: c. 1691-1704

- Charcoal and white lead on blue-tinted paper

- 392x255 mm

- Inscribed: “Conchillos”, in ink at the lower left corner in a 19th-century hand Remains of the date [illegible], at the lower right corner in charcoal

- SOLD TO THE BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON

Juan Conchillos Falcó was born in Valencia in 1641. He first trained with the painter Esteban March from whom he assimilated a typically dynamic Baroque style at the time when the Valencian school still tended to favour the tenebrist naturalism that had prevailed since the early 17th century. On the death of his master in 1668, Conchillos travelled to Madrid, according to Palomino, “to see the famous works and to meet the great men living there at the time.” 1 In particular, Conchillos became well acquainted with José García Hidalgo, who even gave him some of his paintings. 2 When in the capital, Conchillos “regularly visited the academies” and copied paintings by the great masters. He also succeeded in seeing and copying some of the sculptures that had been brought back from Italy by Velázquez and which were housed in the Alcázar in Madrid.

read more

Following his return to Valencia, Conchillos’ work reflects his knowledge of the new, courtly art that he had seen in Madrid. In addition, his work was enriched by the presence of Antonio Palomino in the city of Turia between 1697 and 1701 where he painted the frescoes for the church of San Juan del Mercado. Sadly, little of Conchillos’ painted oeuvre has survived as most of it was destroyed in the Spanish Civil War. Nonetheless, his presence is still to be felt in Valencia and Murcia where he undertook most of his artistic activity. In Valencia there are works by the artist in the parish church of the Salvador, as well as various paintings now in the Museo de Bellas Artes of the city. In Murcia, there is a notable painting of Saint Bartholomew in the church dedicated to that saint. Conchillos’ health declined towards the end of his life and he lost his sight. He died on 14 May 1711.

Given the loss of most of his paintings, Conchillos’ art can now best be studied through the large number of surviving drawings by his hand. These have been catalogued by specialists and divided into three distinct thematic groups: academic studies, preliminary studies for compositions, and landscapes. They deploy different techniques depending on their specific purpose: for example, the academic studies are executed in charcoal and chalk, while the landscapes and narratives (generally religious scenes) use pen and wash. Good examples of the latter include Saint Felix of Cantalicio in the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid, the landscapes in the Museo de Bellas Artes, Valencia, and the five drawings on the life of Saint Thomas of Villanueva in the Museo Nacional del Prado. Conchillos’ drawings thus offer a reflection of artistic practices in the late 17th-century Valencian art world. Since 1670 the city had housed the Academia de Santo Domingo, which followed the precepts of Vicente Salvador Gómez (c. 1637-1680), author of the Manual and fundamental Rules of Painting (1674. Madrid, Library of the Royal Palace). In this text the author insists on the importance of drawing and the use of dark or tinted paper in order to capture more precisely effects of light and shade. All these recommendations are clearly evident in Conchillos’ sketches, which can be seen as examples of both the practice and theory of drawing. 3

The present sketch is an academic study of a man. The body is muscular and well defined but the face is more diffused. The figure is presented frontally, slightly foreshortened to the left, and kneeling. The right arm rests on a rock while the left is raised and tensed in a powerful gesture. Conchillos used charcoal, with which he outlined the figure with rapid, diagonal strokes, creating shadows and emphasising the volume of the body. He also used white lead to create points of light on the figure and to further highlight the musculature. Both the style and technique, as well as the use of characteristic blue paper, are to be found in other drawings by the artist such as the academic studies in the Museo Nacional del Prado, the Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, the Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia and the Louvre, among others. 4 The large number of surviving drawings by the artist seems to demonstrate the truth of Palomino’s comment when he noted that Conchillos liked to execute one charcoal study of a figure every night, noting on them the day and year in which they were executed, and on occasions even the time. 5 This is the case with the present sheet, which is inscribed at the lower right corner, although sadly some of this inscription is now lost. The drawing can, however, be dated to between 1691 and 1704, the period in which Conchillos executed all his academic studies.

[1] Palomino de Castro, Antonio, El Museo pictórico y escala óptica. II. Práctica de la Pintura y III. El Parnaso español pintoresco y laureado. Madrid, 1715-1724 [Madrid, Aguilar, 1947], p. 1132.

[2] Ceán Bermúdez, J. Agustín, Diccionario Histórico de los más ilustres profesores de las Bellas Artes en España. Madrid, en la imprenta de la viuda de Ibarra, 1800, vol. I, pp. 353-355. See also Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E., Pintura barroca en España. 1600-1750. Madrid, Cátedra, 1996, p. 395.

[3] For Conchillos’ drawings, see Espinós Díaz, Adela, Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia. Catálogo de dibujos. I (Siglos XVI-XVII). Madrid, 1979, pp. 64-71; Dibujo Español de los Siglos de Oro. Exhibition catalogue, Madrid, Dirección General del Patrimonio Artístico, Archivos y Museos, 1980, pp. 66-67; and more recently, Espinós Díaz, Adela, Dibujos valencianos del siglo XVII. Exhibition catalogue, Seville, 1997, pp. 210-283; and Boubli, Lizzie, Inventaire général des dessins. École espagnole XVIe-XVIIIe siécle. Paris, Musée du Louvre, 2002, pp. 87-88.

[4] See Espinós Díaz, Adela, Dibujos valencianos del siglo XVII. Exhibition catalogue, Seville, 1997, pp. 68-71, nos. 42-52; and Boubli, Lizzie, Inventaire général des dessins. École espagnole XVIe-XVIIIe siécle. Paris, Musée du Louvre, 2002, pp. 87-88, no. 75.

[5] Palomino de Castro, Antonio, El Museo pictórico y escala óptica. II. Práctica de la Pintura y III. El Parnaso español pintoresco y laureado. Madrid, 1715-1724 [Madrid, Aguilar, 1947], p. 1133.