Spanish Old Master Drawings

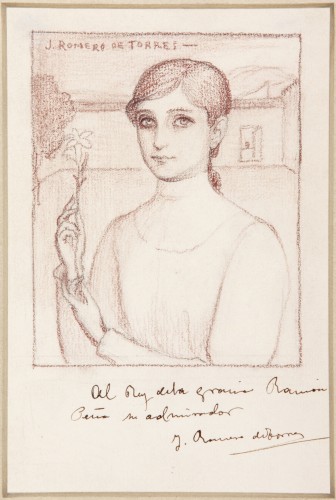

Allegory of Grace

Julio Romero de Torres

(Cordoba, 1874-1930)

- Date: 1920-1928

- Pencil and red chalk / paper

- 190 x 130 mm

- Inscribed: “J. Romero de Torres” (in red chalk, upper left); “Al Rey de la gracia Ramón Peña su admirador / J. Romero de Torres” (in ink, near the bottom)

- SOLD

Julio Romero was born in Cordoba in 1874. The son of Rafael Romero de Barros, a painter and the curator of the Provincial Museum of Fine Arts of Cordoba, Julio Romero was taught painting and drawing by his father from an early age. In 1895 he presented his first work at a National Exhibition in the form of the canvas entitled Mira qué bonita era [Look how lovely she was] (Cordoba, Julio Romero de Torres Museum), resulting in an honourable mention and the acquisition of the painting by the Spanish State. Two years later he competed unsuccessfully for a travel grant to Rome and consequently completed his artistic training in Cordoba. In 1902 and 1903 respectively, he was appointed Senior Professor of Colour, Drawing and Copying at the city’s Escuela de Bellas Artes and Associate Professor at the Escuela Superior de Artes Industriales. In 1903 Romero de Torres moved to Madrid in order to study Symbolist mural painting, the style that he intended to adopt in order to execute a cycle of works commissioned by the Círculo de la Amistad in Cordoba. This cycle comprised allegories of Painting, Sculpture, Music, Literature, The Love Song and The Spirit of Transfiguration (all Círculo de Amistad, Cordoba) and reveals the influence of Puvis de Chavannes. In Madrid the artist soon moved at ease in the city’s cultural circles, taking part in the informal debates at the Café Levante and associating with figures such as Zuloaga, Valle-Inclán, Ricardo Baroja and Gutiérrez Solana, while regularly visiting the Machado brothers’ house. Despite the flourishing cultural ambience in Madrid at this date, Romero de Torres decided to broaden his horizons and travel to England, France, Holland, Switzerland and Morocco. These travels around northern Europe and North Africa marked a turning point in his career that resulted in the evolution of his style. As a consequence, and after his return in 1908, he was awarded a First Prize Medal at the National Exhibition for The Gypsy Muse, which was acquired by the State. He was also awarded the Order of Alfonso X el Sabio and was appointed inspector to the delegation and royal curator at the Rome Art Exhibition. In addition, Romero de Torres won the Gold Medal at the National Fine Arts Exhibition in Barcelona for his Altarpiece of Love, and was made an Academician of the Academia de Ciencia Bellas y Nobles Artes de Cordoba. Based in his studio on calle Pelayo in Madrid, Romero de Torres was extremely active professionally until 1928 when he fell seriously ill. At that point he returned to Cordoba with the hope of regaining his health but died two years later on 10 May 19301.

read more

The present drawing is an allegory of Grace in the form of the bust of a young woman with extremely large eyes holding a flower in her left hand. In the background the wall of a country house and a tree create the setting for the composition. The element that enables the drawing to be identified as an allegory rather than a portrait is the flower that the figure holds in her left hand, pointing to it with her right. This is a freesia, symbolising Grace.

The drawing is dedicated to Ramón Peña2, one of the most famous comic actors of the first third of 20th century in Spain whom Romero de Torres nicknamed El Rey de la Gracia [The King of Comedy]*. The allegory thus makes direct reference to the actor. Peña was an outstandingly talented man, not only on stage, and was the author of various plays including At Three o’clock! The eternal City, and The Wolf’s coming!. He enjoyed enormous critical and popular success due to the “breadth and elasticity of his acting talents that allowed him to tackle both drama and comedy, being equally successful as the leading man in a serious theatrical company as well as in light plays and operetta, [bringing] to each house his particular approach and timbre”3.

Allegorical portraits are common within the oeuvre of Romero de Torres and almost always depict a bust-length female figure, a “strong, self-confident woman like a bronze […] She is the exemplary woman, the woman as symbol”4. The present figure is to be seen again, for example, in Mystic Love (Cordoba, Julio Romero de Torres Museum) and in Good Friday (Cordoba, Fine Arts Museum), although they have different meanings. The woman thus functions as a pretext, as the mere bearer of a message, going beyond what is evident at first sight. Romero used women as “Muses” in his works in the manner of a blank canvas on which he could develop and convey concepts and ideas. His approach to landscape was in some ways comparable and his backgrounds also possess a symbolic significance, always depicting the same type of landscape which is, in fact, that of his native Cordoba. These frozen landscapes, suspended in time, represent the Cordoba of his memories and would enrich his fertile imagination throughout his life5.

[1] A lengthy biography of the artist is to be found in: Exhibition catalogue Julio Romero de Torres. Símbolo, materia y obsesión. Córdoba, 2003, pp. 397-406.

[2] Gómez García, Manuel. Diccionario del teatro. Madrid, Ed. Akal, 1997, p. 643.

[3] Review by Ramón López Montengro for the ABC, April 12th, 1925, p. 71.

[4] Mudarra, Mercedes, “La musa y lo femenino: la incesante búsqueda de lo esencial” in Exhibition catalogue Julio Romero de Torres. Símbolo, materia y obsesión. Córdoba, 2003, p. 93.

[5] There is a particularly interesting essay by De Diego (De Diego, Estrella, “Cartografiando el mapa de Oriente, otra vez” in Exhibition catalogue Julio Romero de Torres. Símbolo, materia y obsesión. Córdoba, 2003), on landscape in the work of Romero de Torres.