Spanish Old Master Drawings

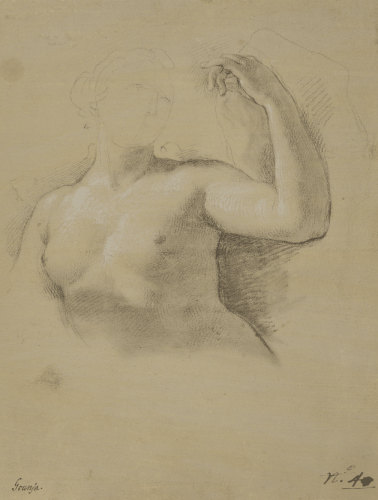

Study for the figure of Venus in the fresco of The Apotheosis of Hercules in the Royal Palace, Madrid

Anton Raphael Mengs

(Aussig, Bohemia, 1728-Rome, 1779)

- Date: c. 1762

- Black chalk, charcoal and white chalk on paper tinted with a greyish wash

- 264 x 202 mm

- Inscribed: “Granja”, in brown ink, upper left corner; “nº 40”, in ink, lower right corner; “Carptª XVIII / 2329”, in black chalk, on the reverse, upper centre; “43”, in pencil, on the reverse, left side

- Provenance: Madrid, collection of the Marquis of Casa-Torres; Madrid, private collection

At the time of Charles III’s arrival in Madrid from Naples in 1759 to assume the Spanish throne after the death of his step-brother Ferdinand VI, work on the new Royal Palace in the capital was almost complete. On Christmas Eve 1734 the old Habsburg Alcázar had been destroyed in a fire and the reigning monarch, Philip V, had decided to build a new palace on the site which would represent the continuity of the monarchy. Charles III found the building small and not to his taste, as a result of which he summoned a new architect from Naples, Francesco Sabatini, in order to undertake important changes to the new palace, changing the location of the staircase and enlarging the building with a Parade Ground in front of it. Once the building was finished and the monarch had moved into it, in 1764, Charles’s attentions turned to the decoration of the interior. The late Baroque decorative schemes executed during the reign of Ferdinand VI under the supervision of the architect Sacchetti and the painter Corrado Giaquinto were largely altered or eliminated. Charles III’s more restrained, classicising taste again led him to commission Sabatini with the modification of the interior decoration, including the stucco work, furnishings, doors, windows and other elements. However, the design and execution of the fresco decoration of the ceilings was entrusted to the celebrated Bohemian artist Anton Raphael Mengs.

read more

Mengs had trained in Dresden with his father, the court painter Ismael Mengs. In order to complete his training, between 1741 and 1744 he spent time in Rome, studying the sculptures in the Belvedere, the work of Raphael and the 17th-century classicising painting of artists such as Carlo Maratta. Mengs returned to Dresden in 1744 and was made court painter but regularly returned to Italy until 1752 when he settled in Rome, acquiring fame as a portraitist and executing important decorative fresco schemes such as The Parnassus in the Villa Albani and the ceiling of the church of Sant’Eusebio. Both frescos reveal Mengs’s full assimilation of the Neo-classical artistic ideal and he continued to deploy this style for the rest of his life. In 1761 he was summoned to Spain by Charles III in order to take charge of the pictorial decoration of the new Royal Palace. 1 Mengs became First Painter to the King and remained in Spain until 1769, working on both the decoration of the royal palace in the capital and the palace at Aranjuez, in addition to painting numerous independent canvases. In 1769 he returned to Rome but was again in Madrid from July 1774 to January 1777. At that date the artist experienced ill health and returned to Rome, although he remained in the service of Charles III until his death in 1779. 2

The most ambitious fresco that Mengs produced during his first period in Madrid was The Apotheosis of Hercules for the ceiling of the monarch’s Antechamber, also known as the Conversation Room, where the King dined. It was also a space for the display of some of the most outstanding works of art in the Spanish royal collection, including Charles V at Mühlberg by Titian, The Cardinal Infante in Nördlingen by Van Dyck and Las Meninas by Velázquez. 3 For this emblematic room, which was principally built between 1762 and 1764, 4 Mengs designed an iconography in which Hercules, here functioning as an emblem of the King of Spain, is received into Olympus by the gods as a reward for his deeds and is crowned by Jupiter. This decorative scheme aimed to exalt the figure of Charles III, not just as a political and military figure but also as protector of the arts, given that it also includes the group of Apollo and the Muses. Mengs created more than fifty figures for this complex decoration, spread across the entire ceiling. Prior to painting the fresco he produced numerous preliminary sketches of both the compositions of the different sides (of which three “façades” survive) and of groups and individual figures. 5 Some are extremely detailed and others rapid sketches, reflecting Ceán Bermúdez’s observation that “while other painters satisfied with their abilities were happy with a light study of a drawing or sketch prior to starting their paintings, don Antonio Rafael devoted months and years to making drawings of each limb, each figure, each group and the entire composition, consulting both nature and the antique.” 6 As Ceán indicated, for the invention of some of his figures in The Apotheosis of Hercules Mengs looked to classical sculpture, the reference point for ideal beauty which offered him a compendium of the sublime. This was the case, for example, with the figure of the god Pan, for which there is a study in the Biblioteca Nacional de España (fig. 1) and which is based on the Belvedere Torso and the Torso of a Faun in the Galleria degli Uffizi. 7

This also seems to be the case with the present unpublished drawing for the same ceiling. It depicts a bust-length figure of Venus, her head slightly titled and her left hand raised and flexed, holding up her mantle to reveal her naked breast. A figure in a similar pose is to be found on the ceiling of the King’s Antechamber (fig. 2). The drawing is executed in a technique commonly employed by Mengs, with a precise use of black chalk and fine, exact lines. The shadows are created with parallel lines while white chalk models and adds nuances to the torso, again applied with very fine lines. These are technical devices widely used in the artist’s drawings, for example figs. 1 and 3 here. The finished bust contrasts with Venus’s lightly suggested oval face, as also found in other studies by Mengs, such as the figure of Venus in The Judgment of Paris (fig. 3). 8 The type of paper, which is tinted with a very light, greyish wash, is again used by the artist in a number of drawings, some of them for The Apotheosis of Hercules ceiling, such as the drawing of Diana and Proserpine (Museo Nacional del Prado, D-003069). As Céan noted, among Mengs’s characteristics was the fact that he “executed his drawings in all different ways, with black and red chalk on white, dark or blueish paper, assisted by the white chalk. He did them in Indian ink, in pastel and in tempera.” 9

Finally, with regard to the inspiration for the figure of Venus, it seems likely that Mengs looked to one of the classical sculptures in the Spanish royal collection; Clytie (fig. 4), a Graeco-Roman work that was considered a masterpiece of art in the 18th century and which had been in the collection of Queen Christina of Sweden’s before it was acquired by Philip V and Isabella Farnese to decorate the palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso. 10 Analysing and comparing the drawing and the sculpture it is evident that the torso, the curve of the hip, the hairstyle and even the position of the raised left arm are all practically identical. The inscription at the bottom of the sheet with the word “Granja”, written in a neat, careful late 18th– or early 19th-century hand thus refers to the sculpture and its location.

- 1.Sancho (1997), p. 515.

- 2.Jordán de Urríes (2006), vol. V, pp. 1530-1532.

- 3.Sancho (2004), p. 101.

- 4.Roettgen (1999), vol. I, pp. 368-369.

- 5.Most of the sketches for this ceiling have been identified and published by Roettgen (1999), vol. I, pp. 374-378.

- 6.Ceán Bermúdez (1800), vol. III, p. 127.

- 7.Jordán de Urríes (2013), pp. 116-119, cat. no. 4.

- 8.Shown with Galerie Arnoldi-Livie, Munich, at the Salon du Dessin in Paris in 2010.

- 9.Ceán Bermúdez (1800), vol. III, p. 128.

- 10.Storch de Gracia (2000), p. 448, cat. no. 6.13.