Spanish Old Master Drawings

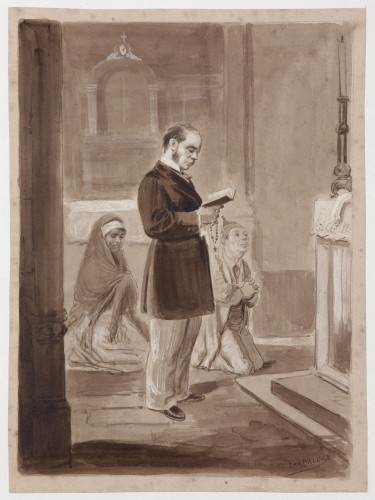

El Calambuco

Víctor Patricio Landaluze

(Bilbao, 1830-Guanabacoa, Cuba 1889)

- Black chalk, wash and gouache on paper

- 272 x 200 mm

- Signed: “LANDALUZE” at the lower right corner

- SOLD

Víctor Patricio Landaluze was born in Bilbao in 1830. His artistic abilities soon became evident and he was first taught by José Madrazo in Madrid. After this, Landaluze went to Paris to learn the technique of lithography. At the age of only twenty he moved to Cuba and settled in the city of Cárdenas. Landaluze intended to remain in Cuba for a short period then leave for Mexico, but having witnessed a bloody uprising in Cárdenas he decided to enrol as a volunteer in the Infantry Militias to fight against any rebellion on the island. This event in the artist’s life explains the subject matter of the earliest drawings that he made in Cuba and which were subsequently reproduced as prints in the studios of Litografía Militar and Louis Marquier. They focus on the subject of The Invasion of the City of Cárdenas.

read more

In 1852 the artist moved to La Habana, one of the most important cultural centres in Central America at that period and a city characterized by the refined social customs of the middle and elite social classes. Landaluze embarked on a lengthy career as an illustrator and caricaturist for the press. 1 He worked for a wide variety of periodicals of the day, including El Almendares, La Charanga and El Moro Muza and his works increasingly focused on picturesque scenes of the everyday life of the humbler social classes. He also produced illustrations for works such as Los cubanos pintados por sí mismos [Cubans depicted by themselves] and was responsible for the section entitled Latest Fashions in El Almendares in which he reflected the diversity and elegance of Cuban society of this period. As time passed, however, and the island’s political situation became more complex, Landaluze’s drawings acquired an increasingly mordant nature as he took the side of the colonial forces against the independence movement that was beginning to take shape on the island. His political stance, however, changed and softened after the execution by firing squad in 1871 of a number of medical students and of the poet Juan Clemente Zenea, who had been a close friend. From that point on Landaluze devoted all his attention to depicting Cuban society and its customs and he expressed the Creole character with a profundity not achieved by any other artist. Landaluze died of tuberculosis in Guanabacoa in 1889, having received numerous decorations (both artistic and military) from the Spanish government. 2

The present drawing, with its precise, elegant lines and attention to detail, is executed with delicate sepia washes. In the centre of the composition an elegantly dressed man wearing a long frock coat and cravat is reading from a prayer book that he holds and from which hangs a rosary. Next to him are two kneeling woman, also praying and looking towards the main altar. The scene is set inside a small chapel that is perfectly defined with only a few lines and which includes a small tabernacle with a sketchily drawn cross on the end wall and a candlestick with a wax candle on a lightly drawn altar table. The male figure corresponds to one of the distinctive Cuban popular types of the late 19th century, known as el Calambuco, a name or nickname that refers to a person who makes an ostentatious show of his religiosity and who, “guided by exaggerated zeal, pays no attention to the most sacred duties and to the happiness of his nearest and dearest, under the pretext of serving God, forgetting that there is a very apt saying that runs: ‘obligation before devotion’”. 3 In the words of José Agustín Millán, whose text accompanies Landaluze’s illustration, el Calumbo, “is generally the first to enter the church and the last to leave it […] he either sells cheap prints of the saint whose feast day is being celebrated or holds a tray and asks for donations for souls in purgatory, who are of as much interest to him as he is himself.” 4

This drawing, which was later reproduced in phototype for publication, is one of a set of nineteen images entitled Tipos y Costumbres de la Isla de Cuba [Popular Types and Customs of the Island of Cuba]. It was published in 1881 and became Landaluze’s most important work. Alongside el Calambuco, it includes colourful figures such as los Guajiros, el Zacateca, el Mascavidrio, el Billetero, el Calesero and los Negros Curros. In this work, published twenty-nine years after Los cubanos pintados por sí mismos – which was criticised for lacking any genuine feel for local culture – Landaluze succeeds in offering an authentic portrayal of Cuban culture through a description of popular types, their habits and professions or activities. Landaluze was able to convey “the Creole soul, the feel of the tropical light, brilliantly suggesting all the joy, passion and astuteness of the customs and tricks, the prejudices and superstitions of real Cubans.” 5 Despite this, Landaluze’s gaze is still that of an outsider and foreigner who was never fully able to identify with the social ideals of the island. Rather than a critical gaze, it is an external, picturesque and on occasions, satirical and caricatural one.

[1] Landaluze’s caricatural drawings have been considered pioneering for the art of the comic in Spain. See Barrero, Manuel, “El bilbaíno Víctor Patricio de Landaluze, pionero del cómic español en Cuba” in Mundaiz. Universidad de Deusto, no. 68, 2004, pp-. 53-79.

[2] For more details on Landaluze’s biography, see López Núñez, Olga, “Víctor Patricio Landaluze: sus años en Cuba” in Víctor Patricio Landaluze. Bilbao, Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, 1998, pp. 9-31.

[3] Various Authors, Tipos y costumbres de la Isla de Cuba por los mejores autores de este género. Obra ilustrada por D. Víctor Patricio Landaluze. Havana, Fototipia Taveira, 1881, p. 174.

[4] Various Authors, Tipos y costumbres de la Isla de Cuba por los mejores autores de este género. Obra ilustrada por D. Víctor Patricio Landaluze. Havana, Fototipia Taveira, 1881, p. 171.

[5] Neumann, Richard, “Víctor Patricio de Landaluce, su obra y su época” in Arquitectura (La Habana), no. 206, 1950, pp. 423-426.