Spanish Old Master Drawings

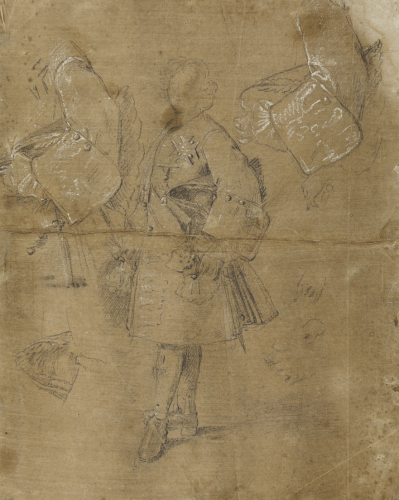

Studies for a portrait of Louis I (recto) Study of two male figures (verso)

Michel-Ange Houasse

(Paris, 1680-Arpajon, 1730)

- Date: c. 1719-1720

- Black and white chalk on light grey-brown laid paper

- 370 x 292 mm

- Inscribed: “20. r.s”, in ink, on the reverse, centre right

- Provenance: Barcelona, private collection

The presence of French artists at the Spanish court increased after the first Bourbon monarch to occupy the Spanish throne, Philip V, imposed his rule following his victory in the War of the Spanish Succession. While some French painters had already entered court service during the reign of Charles II, it was not until around the middle of the second decade of the next century that they started to be regularly summoned to Madrid and appointed to high ranks within the official art system. Michel-Ange Houasse was the first to achieve this new, privileged status following his arrival in 1715 under the protection of Jean-Baptiste Orry. Houasse was the son of René Antoine, one of Louis XIV’s painters and a director of the French Academy in Rome. Houasse himself was a member of the Académie in Paris and his principal function at court would have been to construct an image of the monarch appropriate to the new times while remaining within the tradition of French portraiture. 1

read more

He was the first French artist to receive the title of court painter to the King of Spain and was the only artist to paint portraits of the monarch prior to the arrival of Jean Ranc in 1722. From that point Houasse’s output focused on more lighthearted themes, particularly genres scenes of the type that so delighted Philip V for the decoration of his private rooms in the new palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso. Houasse was a consummate draughtsman who made ample use of this discipline for two purposes: firstly to prepare his compositions in detail, following the traditional academic practice, and secondly to reproduce his paintings for engravings to be made after them. Nonetheless, Houasse’s known output of drawings was not particularly large and in recent years new attributions have been made, expanding the corpus. 2 At the present date around 40 drawings can be securely attributed to the artist. Most are in the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid, having previously been in the collection of Manuel Castellano, and in the Museo Nacional del Prado, which they entered with the Pedro Beroqui Bequest. Many have been cut down and only a very few sheets (in Madrid, London, Stockholm and Paris) retain their original appearance.

This new sheet has dimensions very close to the original ones as it only has slight damage around the edges. In addition to almost retaining its original format it has drawings on both sides: a study for a full-length portrait of a man in 18th-century dress on the recto and two semi-nude male figures engaged in labours of grape harvesting on the verso. This could be seen as a type of summary of the two different themes that Houasse was obliged to embrace in the service of Philip V, here condensed onto a single sheet of paper. In addition, it reveals the artist’s working method and its rhythm as it offers designs for works of different types which can both be dated around 1719-20 due to their similarity with canvases and other securely attributed sketches of that period. For all these reasons the appearance of this new drawing assists in better documenting the high point of Houasse’s career at court and, paradoxically, the progress of some secondary projects that heralded a shift in his career.

The study of the figure on the recto focuses on the clothing and stance of a man whose head is barely indicated. He is shown almost complete, well defined from the shoulders to the feet and located in the centre of the sheet, surrounded by studies of details that cover almost the entire surface of the paper. Two try out similar positions for the left arm holding the hat, which is the subject of another summary sketch at the lower left. In addition, four rapid sketches of the left hand are arranged vertically on the right of the sheet. While these are solely executed in graphite and are intended to try out the position of the back of the hand and the outlined fingers, the other motifs are drawn with different degrees of hatching that creates volume, together with touches of white chalk that produce the highlights and glints on the clothing. This combination of techniques is characteristic of Houasse, as is the maximum use of the paper and the use of coloured sheets of mid-tones such as this light grey-brown one.

With regard to the sitter’s possible identity, not only does his costly clothing indicate his elevated social category but Houasse has also included emblems that signal this high social status, notably the cross of the French Order of the Holy Spirit as well as the Golden Fleece, the private Order of the Spanish monarchy and the Habsburg empire. The characteristic cut of the frock coat (with its exaggerated cuffs from which the ruffled cuffs of his shirt emerge and its pronounced flare from the waist), in addition to the tricorn hat under the arm and the high-heeled shoes with decorated uppers all perfectly correspond to the French fashion of the early decades of the 18th century which prevailed at the court in Madrid. The figure’s pose, which was a standard one in formal portraiture of this period, had already been used by Houasse for a portrait of the Prince of Asturias, Philip V’s eldest son and the future Louis I, painted when the sitter was aged ten (1717. Museo Nacional del Prado, P002387). As in that work, the figure is shown standing very upright, the head aligned frontally and the body slightly turned to the left, with the right foot forward and at an angle in relation to the left one, as in a dance step. It is the decorations visible in the present drawing that allow it to be identified as a study for a portrait of the same prince. Here the clothing has changed significantly since the canvas of 1717 as in that work the young Bourbon was shown as a novice of the Order of the Holy Spirit, whereas here he is shown in court dress.

The Prince of Asturias was depicted wearing the same clothes and with an identical pose in the preparatory drawing that Houasse made for the never executed Portrait of the Family of Philip V, a sheet now in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm (c. 1719, fig. 1). 3 Nonetheless, the relationship between this new study and the Stockholm drawing, although evident at first sight, requires some explanation due to the artist’s compositional procedures. The Stockholm sheet reveals how Houasse “assembled” his individual portraits in order to organise the group portrait of the royal family, 4 and there are, for example, seated portraits of Philip V which the artist repeated in the Stockholm drawing. The collection of the Duke of el Infantado has a three-quarter length portrait of Louis I (fig. 2) wearing the same clothes as those in the present drawing. It is undoubtedly from the artist’s immediate circle and allows for the suggestion of the existence of a lost original. 5 The present drawing could thus have well been used in the preparation of that prototype and not just for the family group in Stockholm. In general terms, it reveals Houasse’s detailed approach to the preparation of his commissions.

Another technical trait characteristic of Houasse was that of making full use of the sheet of paper. This is evident in the rapid sketches of the male figures on the verso of the present sheet (fig. 3), for which the artist turned the paper 90 degrees. These are studies for two secondary figures in one of the artist’s few scenes of the classical world, the Offering to Bacchus, signed and dated 1720 (fig. 4). 6 One is for the young man emptying a wineskin into a large stone vessel of the type used to store wine. He is standing on the pedestal that supports the statue of Bacchus, leaning forward in his effort to pour the libation. The drawing is a summary definition of his foreshortened body holding the full wineskin while the presence of the sacred vessel is only lightly suggested. The body continues down to the thighs and knees, which are not visible in the painting in which the figure has clothes and hair.

In an equally synthetic manner Houasse drew the man who has climbed a ladder in the painting and is putting fruit in a basket, presumably grapes, although the leafy foliage does not suggest a vine. Here the transfer from paper to canvas seems more direct as this is a figure in the shadowy background which is painted in an almost monochromatic manner. The Prado has another preparatory drawing for the painting, which is a sketch of the faun drinking from a small corded flagon in the foreground (fig. 5), 7 executed in the same combination of black and white chalk and on tinted paper of the same type. Interestingly, another drawing in the Prado associated with this painting, of similar characteristics and dating from the same period, also has a magnificent partial study of a man’s frock coat on the verso (D003654), 8 the pose almost identical manner to that of the sitter in the above-mentioned Portrait of Louis I although with differences in the clothing and without any emblems or decorations. This coincidence points to a moment when Houasse was working on two parallel projects for the first Spanish Bourbon monarch, with which the present drawing can be fruitfully related.

ÁNGEL ATERIDO

- Held (1968); Luna (1981); Bottineau (1986), pp. 467-470. For the artist’s relation with engraving and his position within the palace hierarchy, see Aterido (2015), pp. 99-104 and 352-357.

- Sánchez del Peral (2010); Fecit IV, pp. 25-27; Sánchez del Peral (2017).

- Charcoal on paper, 485 x 625 mm. NMH 2844D/1863. Bjurström (1982), no. 977; Luna (1989), pp. 395-396.

- Luna (1989), p. 396; Aterido (2004), p. 50.

- Bottineau (1986), pp. 450 and 585; Luna (1989), pp. 394-395. Photographic library of the Instituto del Patrimonio Histórico Español, Archivo Moreno, 01778B.

- From the collection of Philip V at the palace of San Ildefonso. Aterido, Martínez Cuesta et al. (2004), vol. I, p. 177; vol. II, pp. 407-408, with the previous bibliography.

- Study of a male figure drinking / Study of a female figure. c. 1720. Black and white chalk on brown paper, 183 x 203 mm.

- Study of a male figure holding a pitcher / Study of male clothing. c. 1720. Black and white chalk on brown paper, 270 x 205 mm.